Australia

Australia, often referred to as the “island continent,” boasts a diverse and unique array of ecosystems shaped by its isolation and varied climate. The arid Outback, dominating the interior, is characterized by vast deserts such as the Simpson and the Great Victoria Deserts. These arid landscapes support resilient flora and fauna, including iconic species like the red kangaroo and spinifex grass adapted to the harsh conditions. Moving towards the coastal regions, the eucalyptus-dominated forests of the eastern coast are a distinctive feature on the continent’s ecosystem map. These forests are not only home to marsupials like koalas and tree-dwelling kangaroos but also contribute significantly to the country’s biodiversity.

Australia’s marine ecosystems, outlined by its extensive coastline, are equally captivating. The Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef system, stretches along the northeast coast, harboring an unparalleled diversity of marine life. The colorful coral formations provide habitat for a myriad of fish species, sharks, and marine invertebrates. The coastal areas also feature unique habitats such as mangrove forests, supporting various bird species and acting as crucial nurseries for fish. Australia’s ecosystems, marked by their distinctiveness and ecological significance, face challenges such as habitat degradation and climate change, emphasizing the need for conservation efforts to protect this continent’s remarkable natural heritage.

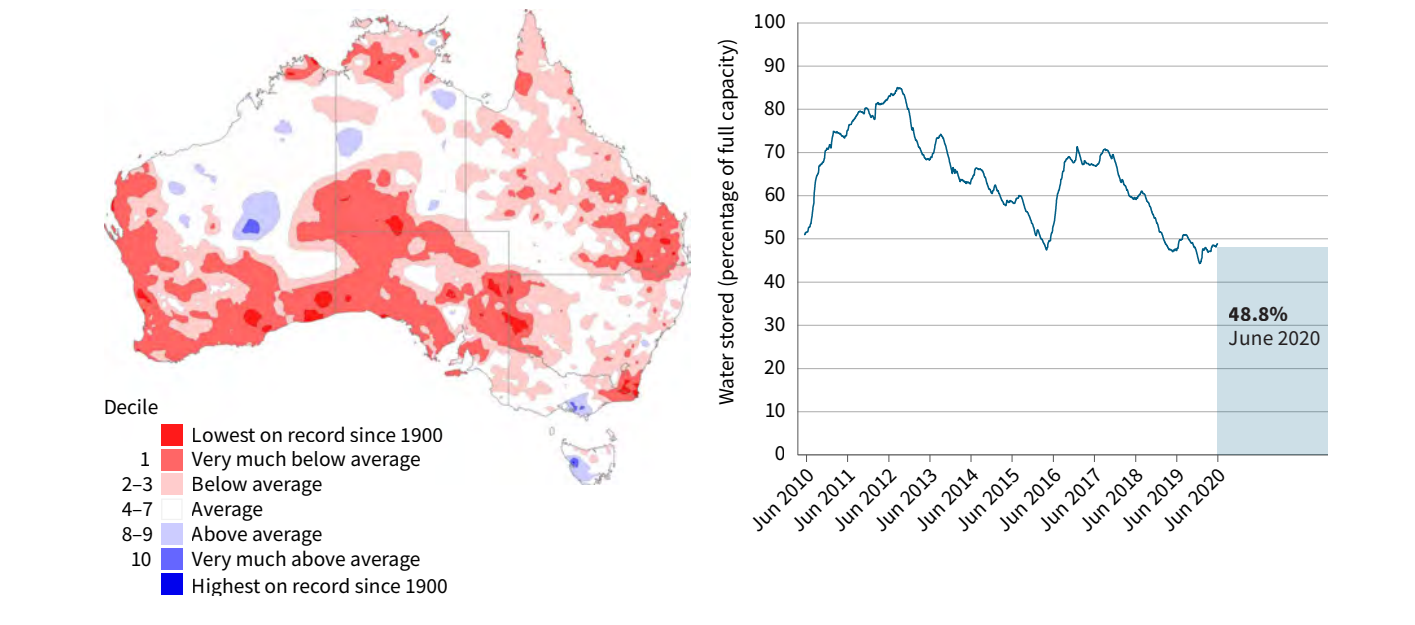

OBSERVATIONS FROM THE MAP:

The map of Australia’s forested areas unveils a captivating landscape marked by a diverse range of ecosystems across the continent. Along the eastern coast, the Great Dividing Range is prominently displayed, hosting eucalyptus forests that stretch across the coastal plains. These forests, with their distinct blue-green hue, provide a habitat for iconic Australian wildlife, including koalas, kangaroos, and a variety of bird species. Further inland, the temperate rainforests of Tasmania stand out as pockets of lush greenery, sheltering unique flora and fauna in the cool, wet climate of the island.

The map also highlights the expansive arid regions of central Australia, where spinifex grasslands and acacia woodlands dominate the landscape. These arid ecosystems are adapted to the harsh conditions of the Outback, providing habitat for species like the red kangaroo and emu. The diverse ecosystems mapped across Australia showcase the continent’s ecological richness, from the tropical rainforests in the far north to the arid landscapes of the interior. The conservation of these forests is crucial not only for the unique biodiversity they harbor but also for maintaining the ecological balance of this vast and varied continent.

Business‑as‑usual periods, outside these extremes, were just as mportant.

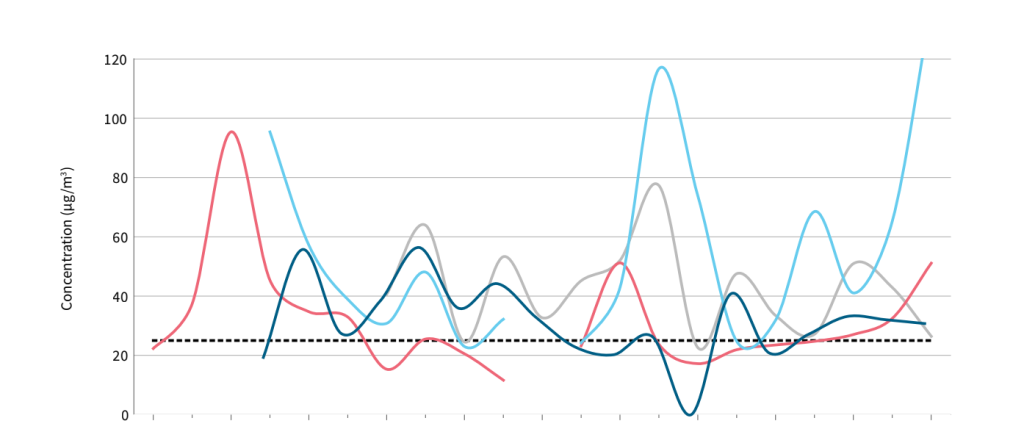

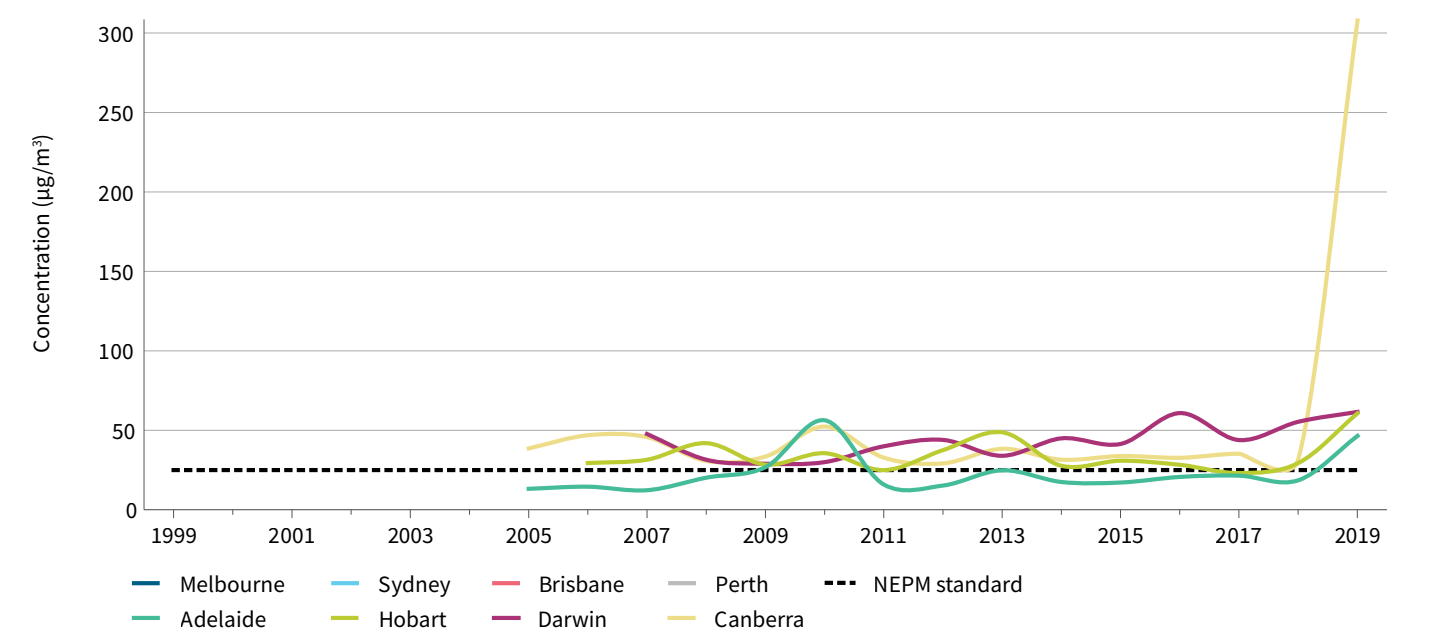

Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is one of the

pollutants of most concern in terms of human

health, linked to 2,616 deaths in Australia

each year between 2006 and 2016, or 2% of all

deaths (Hanigan et al. 2021). Although all cities

have maintained a ‘very good’ assessment for

PM2.5 since 2016, peak PM2.5 levels remained

above NEPM levels in all capital cities in

Australia every year (Figure 3). PM2.5 levels were stable in Darwin, Hobart and Melbourne,

but deteriorated elsewhere.

For concentrations of coarser particulate

matter, PM10, most capital cities maintained

their ‘very good’ assessment grade of 2016, and

Adelaide and Darwin fell just short, moving to

‘good’. Mean PM10 concentrations decreased on

average. The 5‑year trend in PM10 assessments

improved in Brisbane, Hobart, Melbourne and

Perth; Canberra and Darwin were stable; and

PM10 levels increased in Sydney.

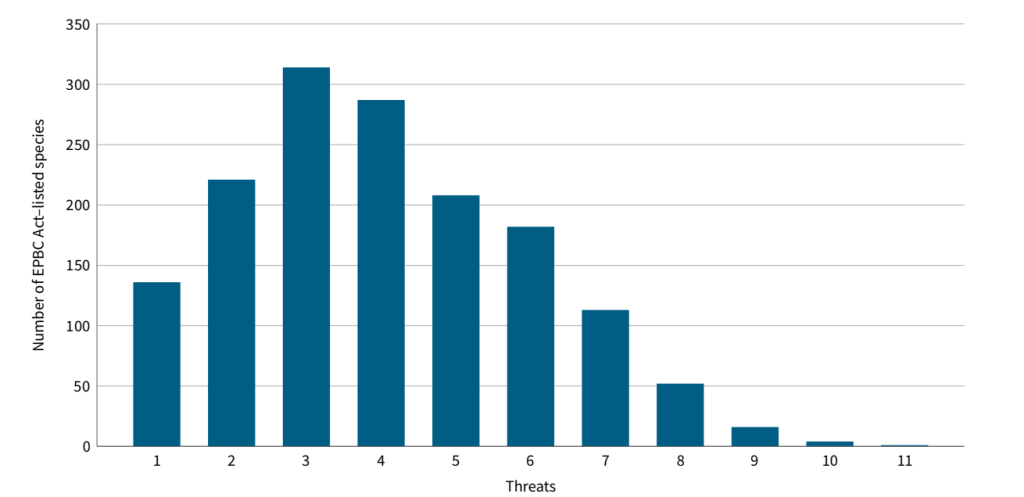

Number of threatened species subject to one or more threats

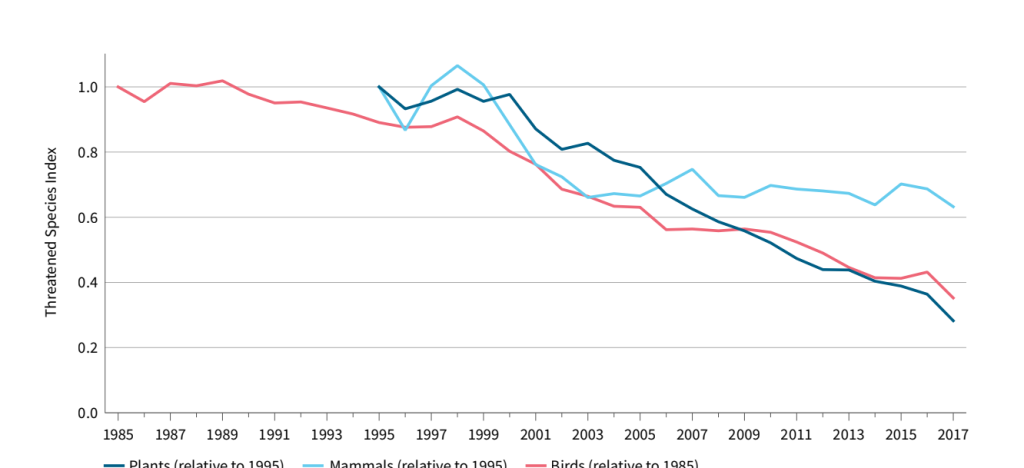

Changes in climate that have been recorded

across the Australian landmass are associated

with a range of biodiversity responses,

including decreases in some species and

increases in others. Alpine ecosystems and

biodiversity in Australia are particularly

vulnerable to climate change that affects snow

depth, and the spatial and temporal extent

of snow, which have all declined since the

late 1950s (CSIRO & BOM 2020). Long‑term monitoring (35 years) of alpine vegetation in Australia has shown shifts in the composition and diversity of plant species, changes in the timing of flowering, and significant declines in endangered fauna such as the mountain pygmy possum (Burramys parvus, which is a specialised alpine species) (Hoffmann et al. 2019)Some threatened species may be considered ‘functionally extinct’, having fallen below the critical number to sustain their populations in the long term. Of the 660 plant species listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered at a national level, 62 are known from fewer than 50 individuals, and 300 from fewer than 250 individuals. These are often restricted to tiny remnants that are vulnerable to further degradation and where population growth is unlikely, with a high risk of extinction within the next 10 years (Silcock et al. 2020).